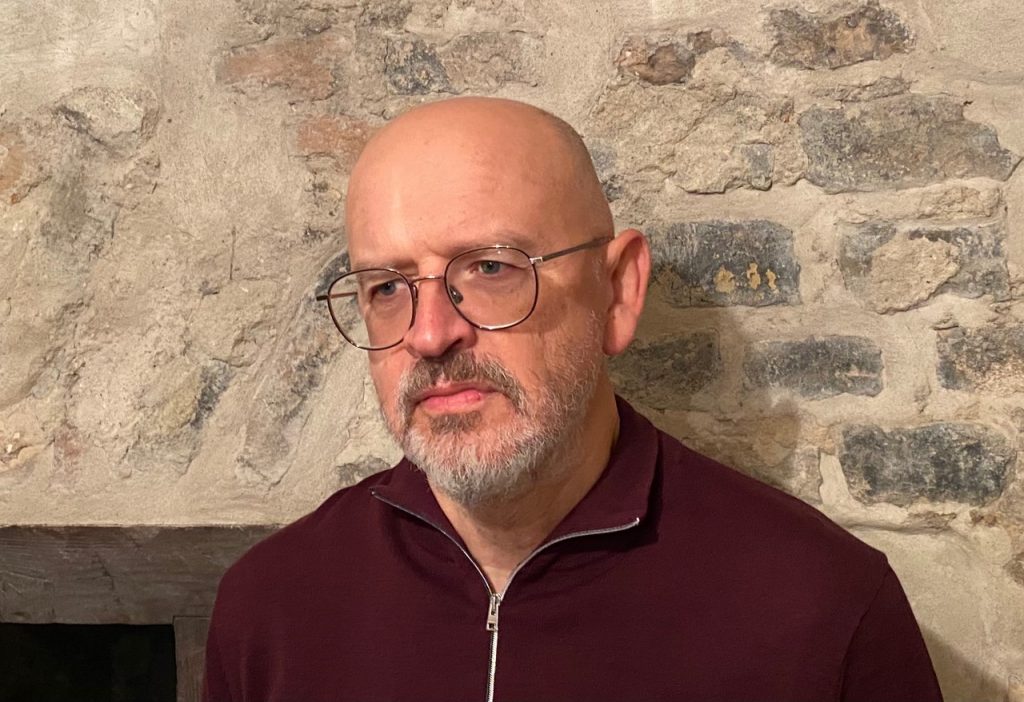

Connecting different viewpoints. Interview with artist and curator Deimantas Narkevičius

This year, the focus of the 68th International Oberhausen Short Film Festival turns to Lithuania. The auteur programme, curated by artist Deimantas Narkevičius and prepared together with Lithuanian Short Films Agency Lithuanian Shorts, showcases works by young Lithuanian artists. The programme “Country Focus Lithuania: Whispering Loudly” consists of three parts and presents fiction, animation and experimental works. Curator of the programme Deimantas Narkevičius was interviewed by film curator Mantė Valiūnaitė.

Mantė Valiūnaitė: I would like to start by asking you about how did the opportunity occur to showcase short films by Lithuanian filmmakers in the International Oberhausen Short Film Festival?

Deimantas Narkevičius: Oberhausen short film festival started to feature – and this would seem rather contrary to their longstanding tradition – national showcases. The first edition was dedicated to Portugal, the second was given to Lithuania. This programme was to be screened in May of 2021, however, Germany was under a strict lockdown and cinemas were closed, so together with the partner of the programme, Lithuanian Short Films Agency, we’ve come to an agreement to ask Oberhausen to postpone the programme I had curated into the following year. We wanted the films to be showcased in cinemas, as well as to provide the filmmakers with an opportunity to present their works in person. We preferred the showcase to become an event. Hilke Doering, the programmer of the international competition of the festival, asked me if I could curate a three-part auteur programme, which would encompass the last decade of Lithuanian cinema. I replied that I would need to think of it, since the task is rather complicated – a variety of very different films are made in Lithuania, and the scene has recently experienced a generous influx of new creators. Moreover, substantial artistic value differences exist among video artists and directors with backgrounds in cinema. I don’t see any harm in it, yet finding mutuality and an appropriate order of appearance seemed as a challenging task.

M. V. Was this task delegated by the organizers of the festival?

D. N. No, it is my personal ambition, since a wide cinema scene coexists in Lithuania. Perplexed by this task, I started looking for advice on where to find one or another piece of work, where to watch them, what works should I draw my attention to. I am very glad that Lithuanian Short Film Agency and its head Rimantė Daugėlaite agreed to help me: they took care of the films, delivery of materials and contacted the authors. Coordinating everything on my own would have been an immense challenge, furthermore, Lithuanian Short Film Agency has worked with Oberhausen in the past. The Agency responded beautifully to my call for partnership, and the result is very pleasing – an institutionally accomplished yet personally curated auteur programme.

M. V. What criteria did you have in mind before starting to watch the films?

D. N. As the practice of Oberhausen shows, it is more preferable for one person to curate the programme. The programmers and curators of this festival select films very responsibly, independently, creatively, and not for representative purposes. They have a longstanding tradition to invite artists and directors to create programmes, which turn into auteur sessions, authentic statements assembled from autonomous art works. This is precisely how I approached this task – it is not a representative programme that one would compile on the basis of criteria such as film awards, festivals appearances or audience numbers. These are the films I liked the most.

M. V. I would love to learn about the principles of selection – did you search for films that would complement the films you’ve favoured, or did you group your favourites according to the topics?

D. N. To start with, I wanted to include experimental films, a genre that slowly starts to take the place of creative documentary. Hence, video artists, who construct their works freely and on multiple layers, had to be included into the programme. Of course, a generation of Lithuanian Academy of Music and Theatre graduates, who are now in their thirties, have enriched the local genre of fiction film; they were also given a large share of screen time in this programme. Nor could I have surpassed experimental animation. I have always been greatly influenced by Lithuanian animation, since my very childhood. I have visited Oberhausen many times to screen my own works, and observed how animation makes this festival only more compelling; animation is included in both, competition and auteur programmes. Such were my main choices genre-wise. The subject of the programme was determined by a question that is very important to me – a question of cultural self, which, instead of deriving from history, is revealed through current social structure: the self that is no longer ethnic, but instead is determined by social and technological factors; culture or subcultures that have permeated states of a multitude of different media. In other words, it is when the vision of our world is being experienced through the screen rather than reality itself – through television, the Internet or other channels of distribution. At first, I found it challenging to take notice of how these realities blend – either in the works of video artists, or fiction films of cinema directors – yet it has become a joining trait that repeats in all parts of the programme. I found it interesting to watch short films by the graduates of Lithuanian Academy of Music and Theatre, as digital expression of a TV related format appears in their works, but it unravels rather creatively. I like it very much – to some degree, it is a hybrid of narrative cinema and TV experience.

M. V. It would be interesting to hear your opinion on the differences of the works presented by graduates of Vilnius Art Academy and Lithuanian Academy of Music and Theatre.

D. N. I wanted to present a spectrum of artistic expressions, one could even say traditions, and thus display how the short film genre progresses. To approach this matter methodically – thus showing what is being taught in one school and another. Of course, the films had to be attuned, and I had to give up several works that I wanted to include for some certain qualities. However, I think I succeeded in placing together different traditions or rather different viewpoints that reveal how the films come about: fiction films, animation or experimental ones. And how the boundaries of genres begin to vanish.

M. V. I find your insight on documentary cinema very interesting, as in the programme there are no films relating to Lithuanian documentary film school as we know it. Just like you said – experimental films are turning into representatives of the creative documentary genre.

D. N. Like, for instance, Feedback by Simona Žemaitytė.

M. V. But this piece is more of a work with archival material, and in my opinion, this tradition tends to be related with experimental cinema.

D. N. This work by Žemaitytė is certainly uncommon, the archive itself is unique. We still tend to perceive working with archives as with something that has to do with analogue film. In this case, it is a personal archive of digital records, and working with material of this kind is genuinely difficult. I agree that in Lithuania, this niche is still quite neglected and not appreciated from the creative point of view. Yet, Simona Žemaitytė is working in this field very resolutely. Moreover, the very archive encompasses a truly interesting period – Kaunas in the 80s, London in the 90s. Only after learning about the acquaintance of Laure Prouvost and Saulius Čemolonkas, I saw how much influence of Saulius’s anarchism is in the early work of Prouvost. I believe this will be a pleasant discovery to the circles of contemporary art that are familiar with Prouvost’s work.

M. V. I must confess, I found rather challenging pinpointing the subject of the second part of the programme. It consists of Agents by Anastasija Sosunova, Places by Vytautas Katkus, Helpless Cure by Miša Skalskis and Milda Januševičiūtė, and The Last Day by Klaudija Matvejevaitė. I have previously seen all of the films, and enjoyed them very much, but I am intrigued to learn how did you see them together.

D.N. I am very glad to have included The Last Day by Klaudija Matvejevaitė. The entire second part of the programme was built with this film in mind. I think that first of all, all of these films are tied by a thread of a certain cultural conflict. The piece by Anastasija Sosunova is about the conflict of “low” and “high” cultures. In the piece by Vytautas Katkus, we see a distinct relationship among people who have been shaped in a liberal environment, but function in urban districts of Soviet legacy. The division between the two mentalities is very distinct – between the common one and one completely digitalized or predetermined by social media. I enjoyed the set up of these encounters, they are both, real and unreal. This “game without an object” metaphor perfectly corresponds to it. Also, the conversations lead nowhere, yet are truly rich – they are very indicative. In the piece Helpless cure, we encounter how young people understand what it means to be elderly. This subject manifests itself through juxtaposition, through playing with children. Big dramatic tension emerges. By the way, this topic has been rarely touched in Lithuanian cinema, especially with such lightness and fluency. There are directors who have made films about elderly people, but without any juxtaposition like the one that we are presented here. I am glad this piece has a musical layer. And the film by Klaudija Matvejevatė is an adaptation of another powerful work, that has, by the way, become such only after this cinematic adaptation. It is a very timely film, and we all must apprehend that the D-Day will come. This day is always near us, and our time is limited. Besides, we have values, not the great values, but the mundane ones, and through the lens of a sudden death, we are reminded that we ought to be precious of everything. It is a very existential work of art. Despite of being made by a beginning student, it has very good elements. And since this is an auteur programme, some connections are emotional – this is how I perceived these works of art.

M. V. Was it important for you to display the aspect of technological diversity of the films?

D. N. I do like the fact that cinema formats have remained versatile. Even though I am quite sceptical of the use of 16 mm at the present time, in Corolla by Gintarė Skvernytė this format has been used very accurately. In her project, blossoms of flowers are placed on eyelids like little sculptures, the material is filmed with a close up lens. This work has the magic of 16 mm film. This silent piece is several minutes long, but becomes a sculpture, and splendidly reveals tension between the moving eyelid and the manufactured plant object. I think that, first and foremost, this piece is feminist – a manifestation of the sense of dignity, but it is also an expression of the fragility of the blossoming nature.

M. V. To be honest, this work helped mе to unlock the entire first part of the programme. I did wonder what this part is about, but after watching Corolla I thought that first and foremost, it is about our relation with the environment and nature. Yet, Dummy by Laurynas Bareiša is also included in this part.

D. N. The plot of his film unravels with lush vegetation in the background, and it dissonates with the scenery – such a brutal story happens in these marvellous surroundings. Bareiša’s film is very dense and intense, and it has been a long time since I’ve seen such an intense narrative cinema. A full palette is presented in the first part of the programme. I needed I Put On the Ivy Crown by Emilija Noreikaitė as a vocalization of the Greek myth. I very much liked the text of this film. And for a programme that is in fact about human relation with the environment, a comprehensive and coherent text was necessary – it allows us to listen attentively to the repeating cycles of Nature without forgetting our own nature.

M. V. In the third part, most prominent is the subject of Soviet legacy.

D. N. Partly, yes. In this part we have an introduction: Man With a Render Animation Camera by Žilvinas Baranauskas, then comes The Juggler by Skirmanta Jakaitė, Techno, Mama by Saulius Baradinskas, aforementioned Feedback by Simona Žemaitytė and Footstones in Night Writing by Emilija Škarnulytė. In this part, we keep returning to the point of departure, yet having obtained a different experience. I myself have been working on this subject for almost 30 years now, but I like how the postcolonial discourse is being constructed from a culturally multi-layered experience. It is no longer regional, no longer linguistic, neither indicative or easily recognizable. It is integrated into memory, into traumatic experience. In my opinion, this programme unfolds the postcolonial discourse through generational differences, allowing us to read completely different social and economic layers. For instance, Techno,Mama is postcolonial, as its fabula contains a conflict with a middle-aged woman, who has not adapted to living under the circumstances of capitalism. It is a social portrait of a lower social layer. However, not the entire generation wanted such an experience. On the other hand, the protagonist is suffocating from the lack of his self-expression, and uses his queer identity, queer culture, and techno music to dissociate himself from the mainstream culture. To fulfil his self, the protagonist is ought to move to a metropolis. But there is also the positive side of it – the conflict between the past and the present is expressed through magnificent architecture, through the environment, sophisticated nightlife and club culture. Director’s work, camera, editing – all very precise. It was simply pleasant to watch, almost leisurely.

M. V. We have discussed the subjects and genres of all three parts of the programme. Perhaps you have observed an attribute that unites the current generation of video art, cinema and animation artists?

D. N. I think this generation is self-critical, it starts to develop a certain sense of humour. I think Lithuanian cinema was lacking of these two elements, or maybe it was well encrypted, and now unfolds to the very essence, like it happens in the works of Sosunova, Katkus, also in Bareiša’s Dummy, which holds irony towards the TV culture itself. A well-mastered TV and cinema language is characteristic to many of the artists.

The 68th annual International Short Film Festival Oberhausen took place 30 April – 9 May. Presentation programme of Lithuania as country-guest at the festival was organized by Lithuanian short film agency Lithuanian Shorts. Institutional partners for the presentation: Lithuanian Film Centre and Lithuanian Culture Attaché in Germany.